Free Associated Events Listed Below

Democracy is in a state. This first UK solo exhibition by Vienna-based artist Katrin Plavčak comes at the start of the year that sees the United Kingdom on the verge of a dramatic break with the European Union. The exhibition of new and recent works will conclude with a live event on Friday 29 March, that will feature the musical trio Chicken (Plavčak, Hoffman, Ganglberger) who will play out the final day – or not – of the Brexit process.

Haus der Lose / House of Lots refers to systems of democracy, practiced since ancient Athens, whereby citizens selected by lot – through random sortition, rather than by public election – actively participate in what still function in certain countries as ‘People’s Assemblies’ that are convened to resolve the major issues of the day. The exhibition is partly inspired by the writings of the Belgian author David Van Reybrouck, whose book Against Elections: The Case for Democracy (pub. Die Bezige Bij, 2013) offers a convincing diagnosis for the failures of contemporary democracy, and makes the argument that our reliance upon present forms of electoral systems to provide us with representative leadership, has led to growing voter disillusionment with an increasingly narrow field of career-politicians jockeying for positions in power, across Europe and beyond.

“Elections are the fossil fuel of politics…if we don’t urgently reconsider the nature of our democratic fuel, a huge systemic crisis threatens. If we obstinately continue to hold onto the electoral process at a time of economic malaise, inflammatory media and rapidly changing culture, we will be almost willfully undermining the democratic process.” from Against Elections: The Case for Democracy by David Van Reybrouck.

Directly engaged within this broad political context, Plavčak works with a sense of both urgency and optimism, offering through her paintings personal visual responses to current events as they occur. As Silvia Eibmayr comments on the artist’s work: “She has a keen sense of the bizarre dystopian and barbaric aberrations that characterize current world events, and without becoming cynical she finds poignant symbolisations for prevalent fears, traumas, aggressions, for malice, helplessness or repression, but also for empathy and political commitment, to specific agendas or individuals” (from On the Mirror of Twilight, Katrin Plavčak, pub. Snoeck 2017).

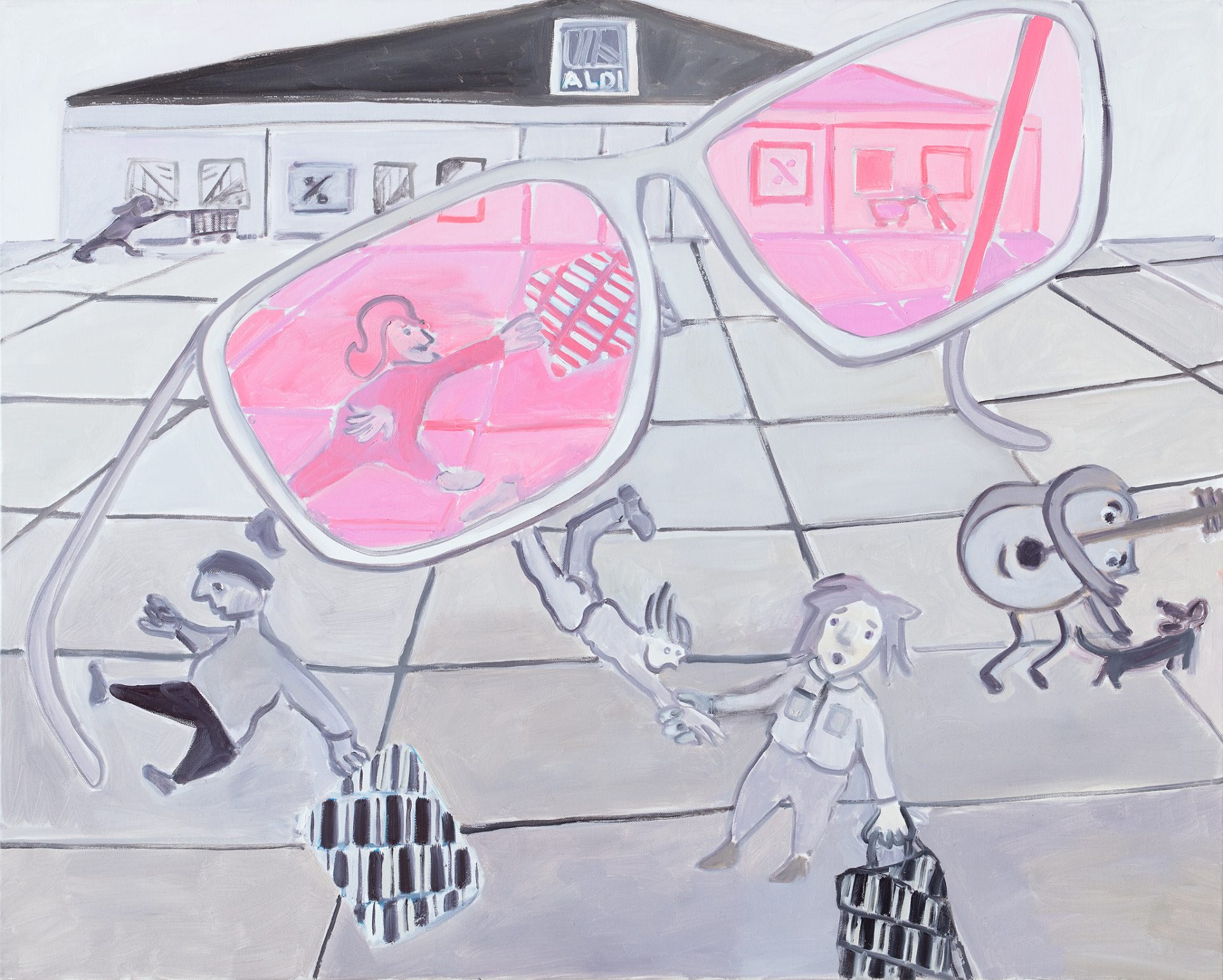

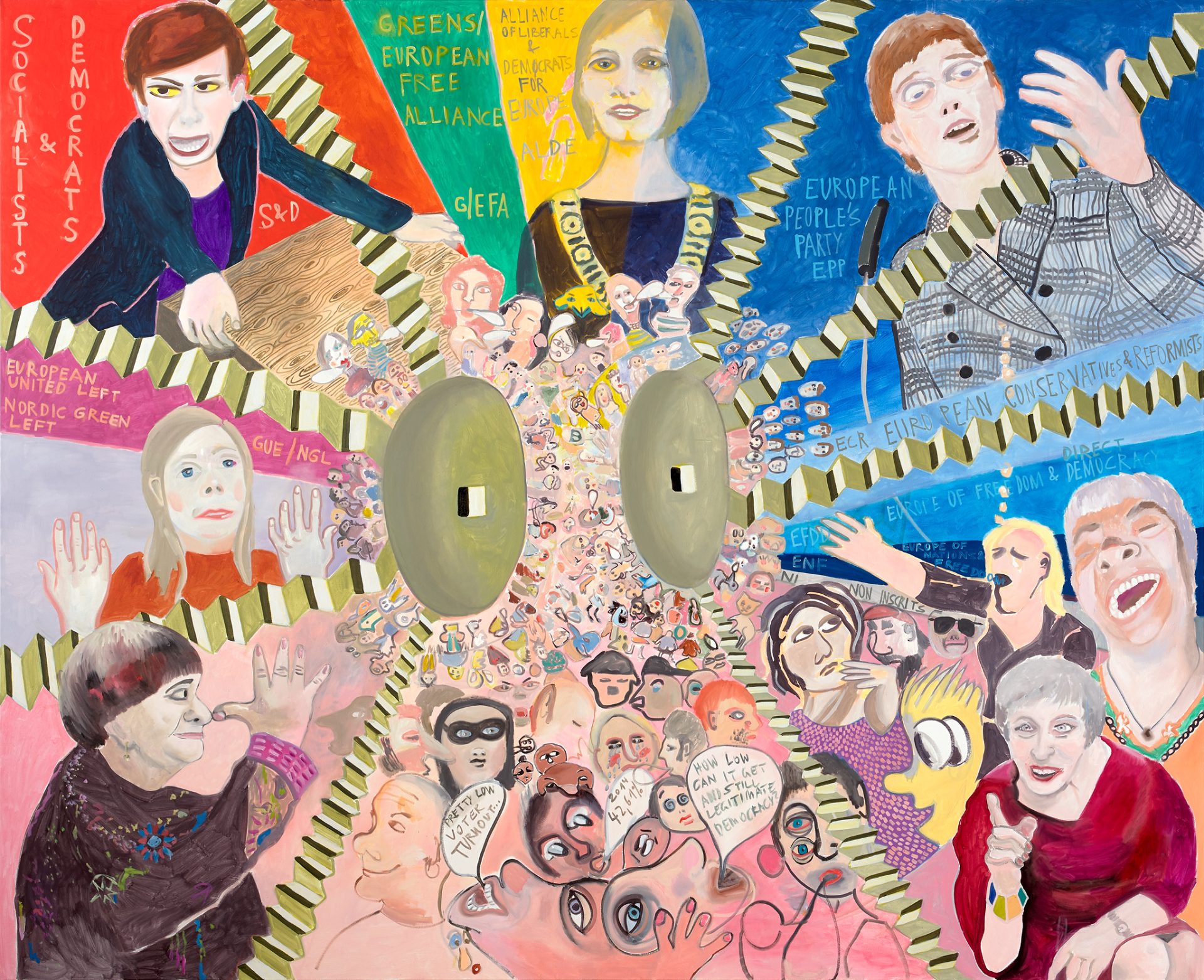

For Haus der Lose / House of Lots the artist paints a contemporary political landscape of carnivalesque horror; a world populated by a cast of grotesquely humorous characters, including real-life politicians, ‘sci-fi’ aliens, refugees, anthropomorphic objects, maps and cartoon beasts. Plavčak, nonetheless, remains critically constructive in her own political beliefs: “The European Union is a unique concept, which started as an important peace project. Yet the European Council seems, more and more, to be the institution which is working against the integration of a unified Europe, unable to find collective answers to the problems the world is facing, like migration, climate change and environmental pollution, digitalisation and the changing working environment. There is an urgent need to come up with solutions for the whole European continent and, by extension, what Buckminster Fuller called our spaceship earth.”

Over the course of the exhibition, in response to ongoing events in the political landscape, the Gallery will be publishing an online dialogue of correspondence between Katrin Plavčak and Dr. Egle Rindzeviciute (Kingston University), with a live discussion on Wednesday 27 February 2019 (see below).

Katrin Plavčak (b.1970) is an Austrian painter and musician based in Vienna. She studied painting with Sue Williams at The Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna, and holds a Diploma from The Social Academy, Vienna. Plavčak has shown at many international galleries and institutions including: the Secession Vienna; Kunsthalle Wien; Deutsche Bank Kunsthalle, Berlin; Kunsthalle Basel; Galerie Mezzanin; Geneva; Marc LeBlanc Gallery, Chicago; Dispari & Dispari, Berlin & Reggio Emilia. From 2012-14 she formed part of the feminist artist group ff and, together with Caro Bittermann and Claudia Zweifel, runs the website The History of Painted Revisited; a growing archive of female painters from art history. Plavčak performs with M.O.G, a sewing machine improvistation duo with Swedish artist Ulrika Segerberg, and founded the band Chicken in 2018 with Nicholas Hoffman (vocals, bass) and Hari Ganglberger (drums), Katrin Plavčak (vocals, guitar). Chicken are currently recording their debut album in collaboration with the Visconti Studio at Kingston University.

Free Associated Events at the Stanley Picker Gallery:

Wed 16 Jan 6-8.30pm: Exhibition Launch / All Welcome

Wed 27 Feb 7pm: Katrin Plavčak in conversation with Dr. Egle Rindzeviciute and Prof. Ilaria Favretto (Kingston University). Drinks from 6pm / All Welcome

Fri 29 Mar 6.30-9pm: Live set by Chicken (Plavčak, Hoffman, Ganglberger) and DJ set by Stanley Picker Fellow Yuri Suzuki. Staged at the Stanley Picker Gallery, in collaboration with the Visconti Studio (Kingston University) / All Welcome

Also: Accompanying the exhibition, Kingston University’s Dorich House Museum is displaying Katrin Plavčak’s painting Is She a Lady? (2015) – a fictional group portrait of historical European women painters. Dorich House Museum is the former studio-home of sculptor Dora Gordine (1895-1991), and now operates as a specialist centre supporting women creative practitioners and thinkers. Special thanks to Marlene Haring & Anthony Auerbach, London, for the generous loan.

Many thanks to: Charlotte Cullinan and Jeanine Richards; Marlene Haring and Anthony Auerbach; Michael Gatt and Pol Jesperson, Liam Guest, Louis Peckham, Ben Williams and Samuel Johnson at Visconti Studio (Kingston University); Ilaria Favretto and Egle Rindzeviciute.

The following email dialogue between artist Katrin Plavčak and Dr. Egle Rindzeviciute (Kingston University) is published below online, as it develops over the course of the exhibition. A live discussion between Katrin Plavčak, Dr. Egle Rindzeviciute and Prof. Ilaria Favretto (Kingston University) takes place at the Stanley Picker Gallery on Wed 27 Feb from 7pm / All Welcome.

22.01.2019:

Dear Katrin,

Congratulations on the opening of Haus der Lose / House of Lots at the Stanley Picker Gallery.

I am very keen to hear more about the background of this project – what led you to choose this topic?

Also, I was wondering, in what ways can painting as a form of “high culture” participate in the debates on the character and state of liberal democracies?

With kind regards,

Egle

25.01.2019:

Dear Egle,

A year ago I moved back to Vienna after 15 years living in Berlin. One reason why I went to Berlin in 2002 was that the right wing party of Austria (FPÖ) got so many votes by the people living and allowed to vote in Austria, that they could establish a coalition with the conservatives (ÖVP), and then formed a centre-right government. Even though the ÖVP didn’t get the most votes (the social democrats won the elections), they landed a coup with building a coalition with the right wing party (W.Schüssel / J.Haider). For me, it was unbelievable that in a country which was also responsible for the Holocaust, one third of the population was voting again for a party (FPÖ) with a racist and discriminating ideology that is the home of the ‘fraternities’ which, via the FPÖ, have been able to get into Parliament. These fraternities are the home of the Nazis in Austria, and the relationship of the fraternities and the right wing party FPÖ is very close.

Now, 15 years later, Austria again has a centre-right government. People seem to forget how quickly this coalition of a centre-right government enriched itself the last time with the money from taxpayers, and how their criminal activities are still keeping the courts busy in Austria today.

S.Kurz (ÖVP) changed the colour of the conservative party from black to turquoise and again, like Schüssel, chose a coalition with the right wing party FPÖ (H.C.Strache) to gain power. Since this government has been in charge, they immediately changed laws, rebuilding the state institutions, reversing the aims of progressive education, cutting rights for foreigners, and pushing the borders of language in a direction which should have been forgotten a long time ago.

The Austrian composer Georg Friedrich Haas explains well, in his text ‘Monolog für Graz‘ 2018 (a piece he wrote for the Musikprotokoll), how the Nazi ideology survived in Austria and how the parties have managed to put their people in places of power.

So this is the background of the country I happen to live in now, and the passport I carry. I consider myself a citizen of Europe, and every Thursday in Vienna there is a big public demonstration against this government, organised by great people of different occupations and backgrounds.

All over Europe right-wing ideologies are gaining power; or to be more precise, nationalism in the form of right-wing populism. I was looking for authors with critical minds and with answers to what could cause such a drift to the right of so many citizens of the European Union. I came across the writer David van Reybrouck and his book ‘For a Different Populism’, where he describes how more and more people in Western societies, of lower education and income, are rejecting taking part in voting as a democratic process or follow right-wing populists, as they no longer see themselves represented by their parliaments.

This led me into the topic of how democracies are legitimized, and how the democratic process has changed over its long period of existence. In his book ‘Against Elections’ Van Reybrouck suggests some kind of lottery as an additional tool for voting and find a democratic way to translate the will of citizens into laws. He talks about deliberative democracy to develop public discourse about all political topics. In this way citizens are provided with direct access to democratic participation and this returns their faith in the system.

(ER: Also, I was wondering, in what ways can painting as a form of “high culture” participate in the debates on the character and state of liberal democracies?)

I hope that painting doesn’t float away up in the skies, far away from practical political developments. I think one of the most noble, and therefore ‘high’, cultural achievements of our society is the political construction of a democracy. It assures citizens that they are equal, that they have the right to vote, and be a part of the process of defining their own government.

I have always thought of painting as a form of communication, as information, and in this sense it is able to talk about political circumstances. And it always did. A long list of painters over the centuries have produced images of the contemporary ‘powerhouses’ of their times – in part because they were the ones paying for it – and painting big political events. If we think of Goya, he painted the Spanish royal family in a very ironic way, and also the cruelties of war, which can be easily read as social critique. Painting is deeply connected with capital and the political powers in charge.

Painting is a tool for me to deal with topics I am concerned with, to help me think about them, and for me to provide quick reactions to political developments and express the status quo.

Friendly greetings,

Katrin

28.01.2019:

Dear Katrin,

You mentioned that you paint in response to the events happening around you, reflecting on the issues that are presented as the most burning ones on the political agenda. One thing that struck me particularly when seeing your exhibition was the bright colours and the vivid, painterly quality of your works. There is, I think, a very bright energy pulsing from your canvases. How do you make aesthetic choices when approaching such charged topics as the failures of the political systems?

With kind regards,

Egle

05.02.2019:

Dear Egle,

Painting is a method to think about certain topics for me. I guess it’s all about charging a work, during the painting process, with content and form. I try to understand something, and while painting it, I can get very close to the subject matter. I guess it’s also a way for me to digest politics.

Colour relationships are very complicated. Like Bridget Riley has stated, as soon you change one parameter of one particular colour, the whole enterprise starts moving. Also, colours make a strong physical impression on me, and hopefully to other observers, especially in the presence of bigger paintings, which I believe not only happens through the eyes but also through the body, where colours talk to my cells directly, like music.

In the painting The European Republic (The Lady Facing Afrika), I chose many different shades of blue – Paris Blue, Prussian Blue, Coelin Blue, Indigo – to paint one woman as a personification of Europe. There are many ways to describe and understand the same situation, so by representing Europe as a person, it is perhaps possible to develop an emotional response towards her; to try to fall in love with an idea, as Ulrike Guerot puts it in her book ‘Why Europe Should be a Republic; A Political Utopia’ (Piper 2017). Chantal Mouffe also talks to my understanding of this idea, when she points out that art could play an important role in establishing a left populism, because art is able to create affects or emotions:

“This is the big power which lies within art; the ability to show us things in a different light and to make us realise new possibilities.” Chantal Mouffe ‘For a Left Populism’ (Edition Suhrkamp, 2018).

In my painting, Europe is a woman who is hoping that the progress of emancipation and feminism will create new solutions for a European Republic, not dominated by one nation pursuing hegemonial power. One human body; the arm, the leg, the head and the heart all need to work together. Every part on its own is very specific – like the different regions of Europe – but they would have a sad and isolated existence on their own.

A very important role that Europe has to define anew, is its relationship with Africa, and the historical responsibilities we have towards our neighbouring continent. We have to find a solution which is not a concrete wall with barbed wire, or a sea where people who try to escape from no future, face death. We are obliged to deal, in a human way, with refugees coming to us from this continent, and in my painting Europe is unsure how to face Africa, and she looks, afraid, into the eyes of the black continent, which is so close on the map, yet so far away in the hearts and heads of European people. Colonialism then and exploitation now; African workers held like slaves in Southern Europe today, and nations, like France, not acknowledging the population of their former colonies as citizens of their own.

With friendly greetings,

Katrin

11.02.2019:

Dear Katrin,

Thank you for your thoughtful and stimulating response, and apologies for my delayed answer.

I was, coincidentally, travelling in Brussels, visiting the House of European History among other things. This museum is indeed trying to engage with the history of Europe as a totality of the nation states that comprise it. The exposition starts with the myth of Europa and ends at a hall, situated on the top floor, which already contains a display of Brexit voting ballots and campaign materials for both Leave and Remain. There is also an exhibit of safety vests, to acknowledge the ongoing crisis of refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

While the museum speaks through objects arranged into illustrative sequence, to flesh out narratives scripted by historians, your paintings attack all senses and taking the command of the viewer by their sheer size, as you said earlier.

This made me think about the invisible, but important, role of technology, that determines the way in which we sort our information and images. I do not remember the last time I printed out a photograph, let alone a large size print. Images come to me in a screen size, and screens are compact, small and portable; perhaps like stereotypical judgements that are quickly and conveniently produced by the mind. A large size painting demands one to pause and to physically orient oneself in the space. Not so with the screen.

I heard that you reflected on social media by painting a few pieces that were intentionally smaller in size, in comparison to your large paintings not to the size of my laptop screen. I would love to hear more about the idea behind these paintings and how they originated.

With kind regards,

Egle

15.02.2019:

Dear Egle,

That’s a beautiful comment you make here, about the difference of perception between paintings and photographs, in delivering political content. It has to do with the time it takes to look at a painting and the physical presence of the image-object. You can’t scroll over a painting (yet!). The size, plus the time it takes the observer to look at an image and think about it, makes a big difference.

We still tend to believe that if we see a photograph we are confronted with facts and reality. A painting doesn’t promise to talk about truth and reality. Here we are in the realm of paint. As a viewer of a painting you are always aware that you look at the opinion of a painter – as long this painter is not called e-David (AI).

The fact is, we live in times of fake realities. Well-founded journalism is so important for democracy, but needs time for research and investigation. Journalists need to get paid well and need the support of a free society. Increasingly, citizens are getting information from Facebook and such, misinterpreting this for truthful information, and getting more easily manipulated.

I am not on Facebook, but I do use Instagram. When I started posting things, I got so curious about reactions; it’s such a strong trigger, very human. What a weird mixture of curiosity, advertisement, public and private. And you give away a lot of information of yourself and your habits, even if you try using social media as a publicity tool for exhibitions and music-shows. I started feeling very uncomfortable about it.

Actually, just one of these three small paintings in the exhibition is called Social Media – a more or less stressed-out face trying to idealize itself with tiny hands. The other two are called Pepsi and Lean On. If you want, you can read these three together as function-images when looking at Instagram: self-manifestation, desire for human closeness and product-placement.

Our data gets collected, processed and analysed, and these masses of data are not sorted out by humans, but by algorithms. I believe that these tons of data are also used by self-learning algorithms, to understand how humans work, how we think and how we feel. I think they want to learn how our emotions are functioning. In the present, social media is used to influence political decisions and voting habits of the citizens. I guess in the future data-information will deliver a tranparent image of humankind for real and virtual machines.

Friendly greetings,

Katrin

19.02.2019:

Dear Katrin,

Thank you for your thoughts. I am typing this in a hushed reading room at the Cambridge University Library, a beautiful place where a few old-fashioned card catalogues are kept in the corridors. However, the algorithms are everywhere and need to be reckoned with. The University of Cambridge hosts the Future Intelligence Institute, which gathers many scholars from what could be considered as traditional fields of humanities and social sciences to re-think the meanings of human and non-human agency, the history of intelligence assessing the political impacts of the increasingly effective algorithmic technology.

At Kingston University, Prof Felicity Colman led an important research project that investigated what she and her colleagues described as “the algorithmic condition”. Drawing on both Hannah Arendt and Francois Lyotard, Colman and her team assessed the origins of the algorithmic condition and probed the ways in which this ever expanding digital reality could be subject to ethical judgments and regulations. Their wise suggestion is to develop a basis of “ethical environment” – a social and material system of awareness of the algorithmic condition itself. Such an ethical environment could emerge as the result of education, but also of a “societal ethos”. It strikes me that there is an important role for the art to play in the development of a societal ethos for our politically disturbed and disturbing algorithmic condition.

This said, the relative feeling of containment that paper card catalogues and neat rows of books communicate is a deceptive one. History is only too full of examples of mass violence, the implementation of which was mediated by lists of names printed on paper…

The link to the report is here: https://ethicsofcoding.wordpr ess.com/2018/02/20/ethics-of-coding-the-algorithmic-condition/

With kind regards,

Egle

23.02.2019:

Dear Egle,

Yes that’s indeed a very uncanny aspect, that machine learning is being used to deploy bots on social media (social bots) so that can build misplaced trust, harvest personal information, and spread propaganda; how Dr. Thomas King, of the Digital Ethics Lab at the Oxford Internet Institute, writes in the report you sent. And that these machine learning techniques, which can be beneficial to society, in the fields of crime prevention and medicine, are being used to harm the infosphere. So the first big step is to become aware of the algorithmic condition we are living in and then ascertain and implement ethical regulations.

Maybe another reason to think of extending our democratic tools in the direction David van Reybrouck is suggesting in his book Against Elections. He is arguing for a stronger participation of citizens in democratic procedures, which also means a deeper involvement in the knowledge of topics of politics and society. He writes about finding the opinion of the population not only through elections, because they can be manipulated by misinformation, but also by sortition or election through lot.

Deliberate democracy means more participation of the citizen, and if we as citizens are more involved in the act of naming and working on topics which have to get organised by the state, then these decisions will be backed much better by the population.

How do you think that art could play a role in the development of a societal ethos for our politically disturbed and disturbing algorithmic condition, as you put it? Do you think art could create more awareness for this problematic development? Through creating images which are circulating not in the digital but in the real world? Lots of places where art is shown are rather elitist and just a small segment of the society dares to step into a gallery or contemporary art institution. Also, many artists don’t want their art to be seen as a tool for propaganda, and don’t want to get labelled as political artists. Making art doesn’t make you an ethical person. I think its crucial nowadays, where right-wing populism is growing like a disease everywhere, that politics has to construct a frontier between ‘us and them’ like Chantal Mouffe says, and that its necessary in these critical times to point out that our opponents are not the refugees coming in but the oligarchy.

I think a very important human strength for the future will be fantasy and resultant innovation. This could be a role for artists, who are able to imagine things and, as a consequence, invent things. I guess algorithms collect information, compare it and build variations. Also humour is a big human benefit, which machines, I guess, are not capable of.

But maybe machines don’t need humour, because they don’t have taboos and suppressed memories. Yet.

Friendly greetings,

Katrin

To be continued…